Studio Devona

Studio Devona - Devon's Old Trackways

Devons Old Trackways

For 11 years from 2014 I made an extensive study of how trackways evolved in Devon. My

aim was to see if I could work out where the oldest tracks in the

county were and when they came into being and why - perhaps to even find

some long lost features such as sacred sites, lost wells, Roman roads

or important places where trade took place on main ancient routes - my

study was intense taking many hundreds of hours and I learned a lot. This is still to be an ongoing project. On this page I share my interest and some of my findings and I am happy to chat about this topic: studiodevona@gmail.com

How the trackways Began

Sometimes on a calm evening as the sun goes down I will sit and ponder on how the place I live might have once been

long ago compared to how it is now. I think about how we travel around so easily in our cars, never thinking too

much about how we pass over miles of land while just popping out to a local shop or visiting a place we like. How different

it would have been say 600 years ago, or even 2000 or 5000 - and yet how similar and familiar some aspects would be.

I can only imagine sometimes how someone would have sat exactly where I now sit and look out over

the Devon hills and watch the sun set. Perhaps they wondered about who might sit where they did some distant day

in the far future and what they would think.

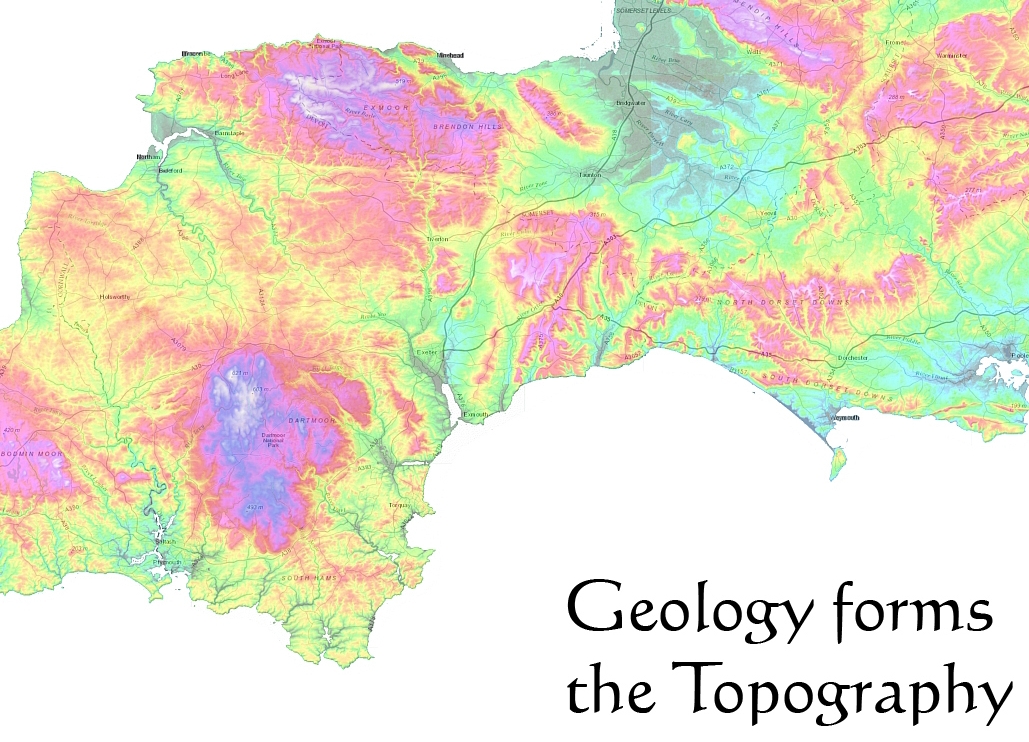

I can imagine what Devon might have been like long ago in part by the shape it is today and the topography of the

landscape - the underlying geology and how it has been eroded for millions of years is what gives us the canvas upon which civilization has evolved. I hear the sound of rivers, and that of the sea shaping the coastlines which have echoed through time unchanged, also the soft summer breeze that cools the air after

a long hot day and the howling of a gale whistling through the cracks in the rocks on a high Tor.

But long ago there would be no loud noise as we know it today - the endless toil

of car engines with horns hooting, motorbikes,

trains, aircraft passing overhead. Yet there would have been more

familiar human cries and cheers, laughter, the sound of horses,

cows and sheep, and of course birds and other wildlife. Also the sound of wood, metal and stone being shaped, and the cry of turmoil in times of war.

I imagine a way to think of Devon long ago might be to compare this land with that of a wilderness in our world today, although

there are few of them left but thankfully some.

Let's imagine Devon as it might have been a few thousand years ago

when it was less populated. It was much the same as it is today in some ways but there would have been many more trees of course and meadows full of flowers. Wild

animals would roam too and fro just as they do today in those wild places on earth.

People and animals have basic

needs such as food and water, and shelter from harsh climates and there would have been special places where animals

congregated with predators watching over them. Indeed we know that Devon has a rich history of such from the evidence

found in old caves in the region which have revealed the bones of Lions, Mammoths, Woolly Rhino and Hyaena to name

a few. These creatures and the passing through of hunter-gatherers would have been the first to have created pathways

through Devon's landscape and it is from those early routes that perhaps some of the layout of Devon's present roads would

have come about, maybe still in use today.

In such a primitive landscape there would have been some special

features that stood out. To early people living

in the region, places would have been familiar to their every day life

like the sights and sounds of nature around

them, the cliffs, the rivers, the sea, and the trees. There would have

been also places of joy and fear, of respect, places

of rejection, places that people related to emotionally just as we do

today. There would have been caves

leading into the bowels of the earth, springs where essential water came

from the earth, Tors and other rock clusters that stood out above the

tree tops almost as God-like

beings. And of course those awesome aspects - the sun and the moon and

the stars.

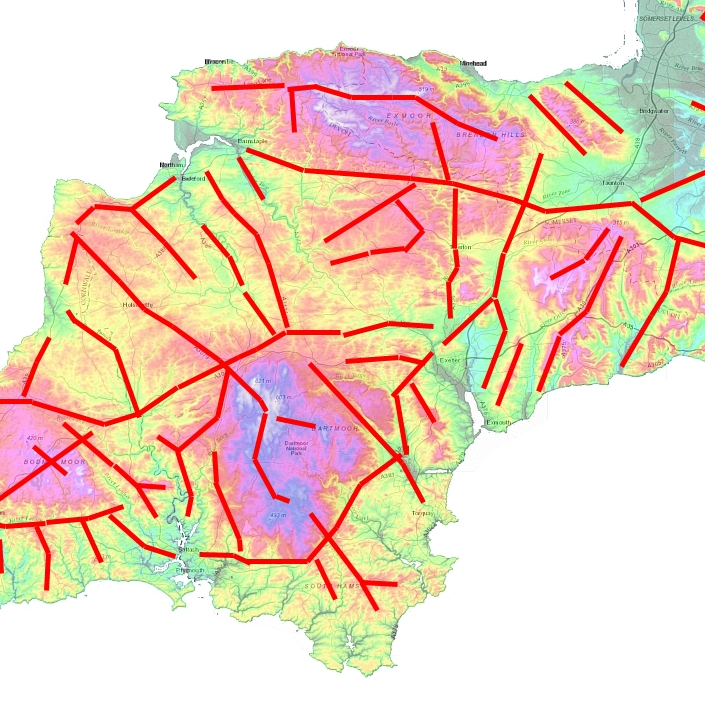

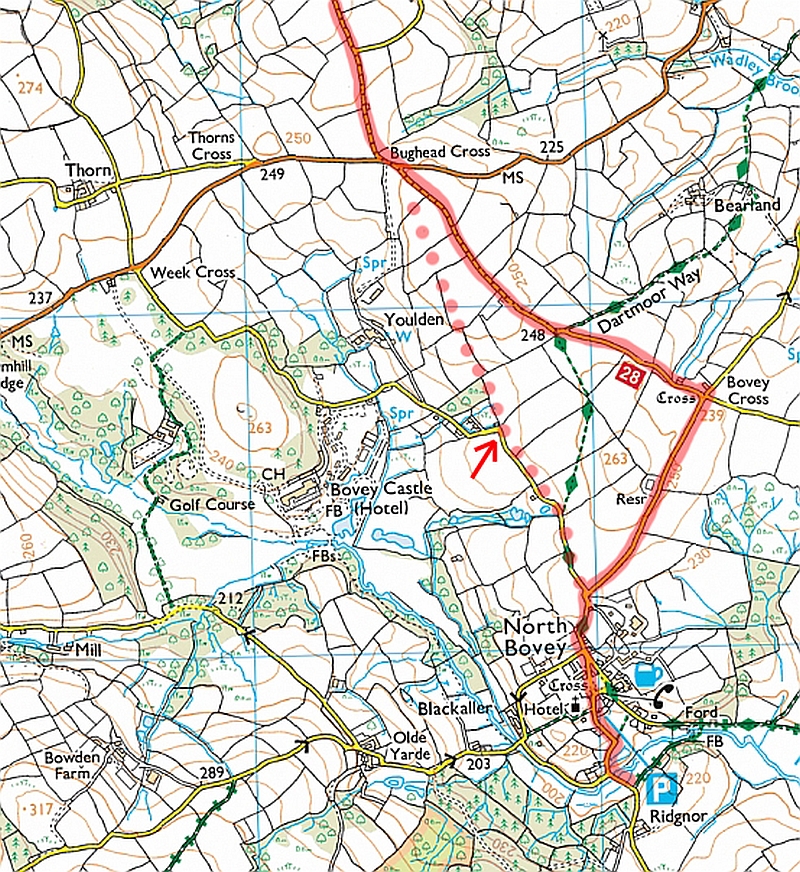

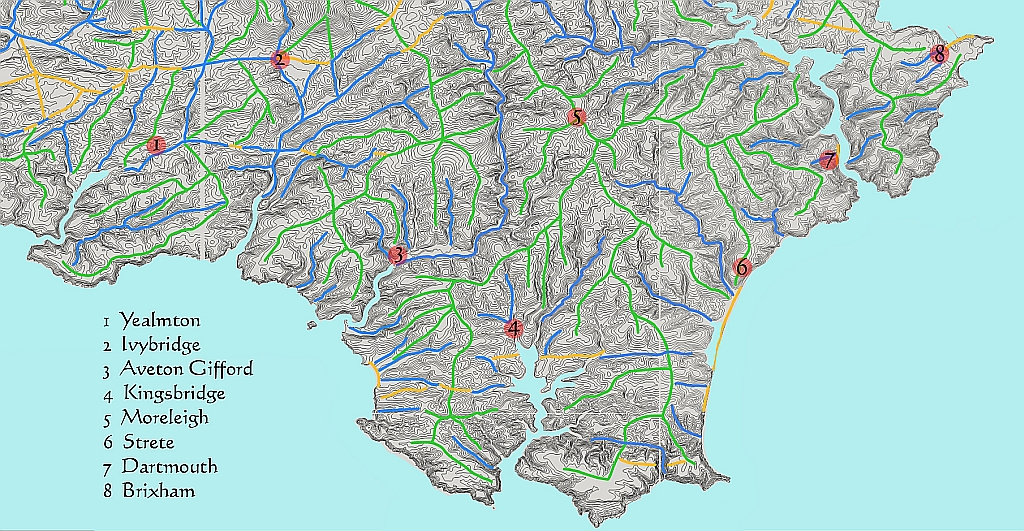

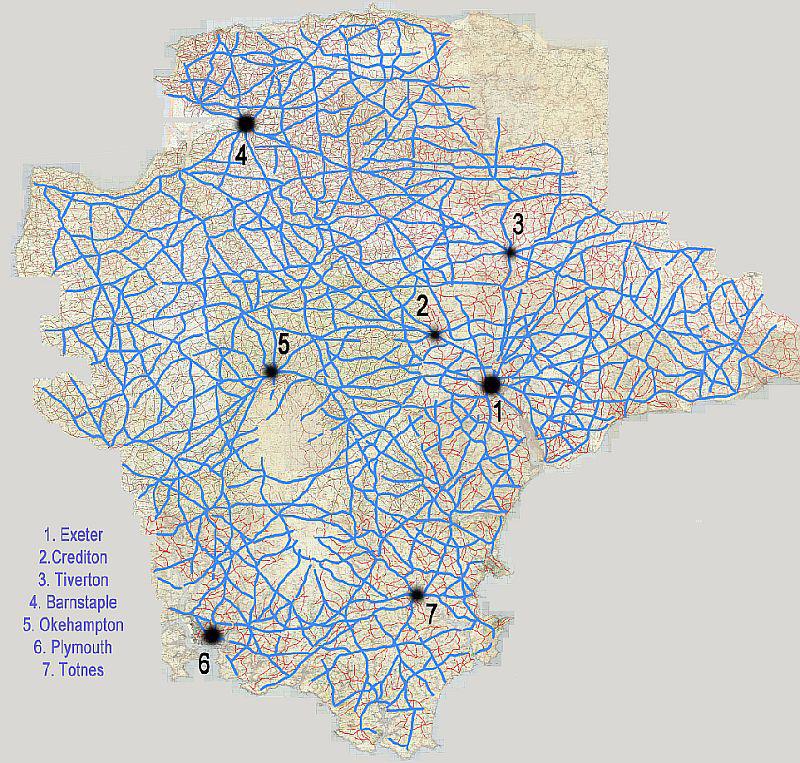

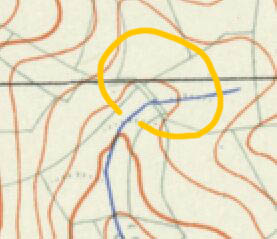

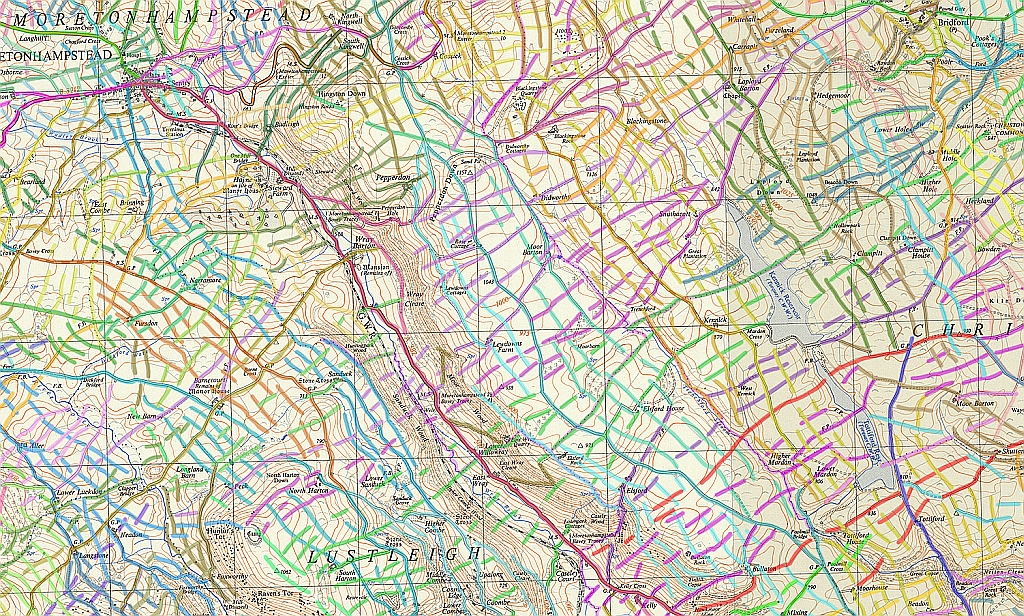

In an effort to try and understand the very basic ancient routes in the Westcountry I used a topographic map of England and

drew on some lines. The map here is what I came up with and I have not taken into

account sea routes and I have not used known Roman roads - all I wanted to do was understand the topography and see what

might come to mind. Obviously also there would have been various tribal settlements which would have influenced routes and

I have not taken these into account either.

From my basic findings I have concluded initially that there was a main spine route that ran the length of Cornwall (much as

it does today) and that it followed a course around the north of Dartmoor past Okehampton and headed towards Wellington in Somerset.

Another branch crossed north Devon skirting the south of Exmoor. Another branch would have passed through Exeter then found a

way around the south of Dartmoor to Ivybridge and Plymouth (again as it does today). Somewhere in the region of Wellington routes would have split and gone to

Dorchester, Salisbury and Bath to the east.

Map: Shows what I think would have been the really basic routes in

bold red.

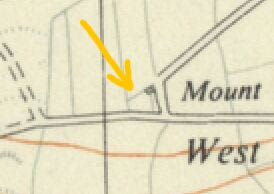

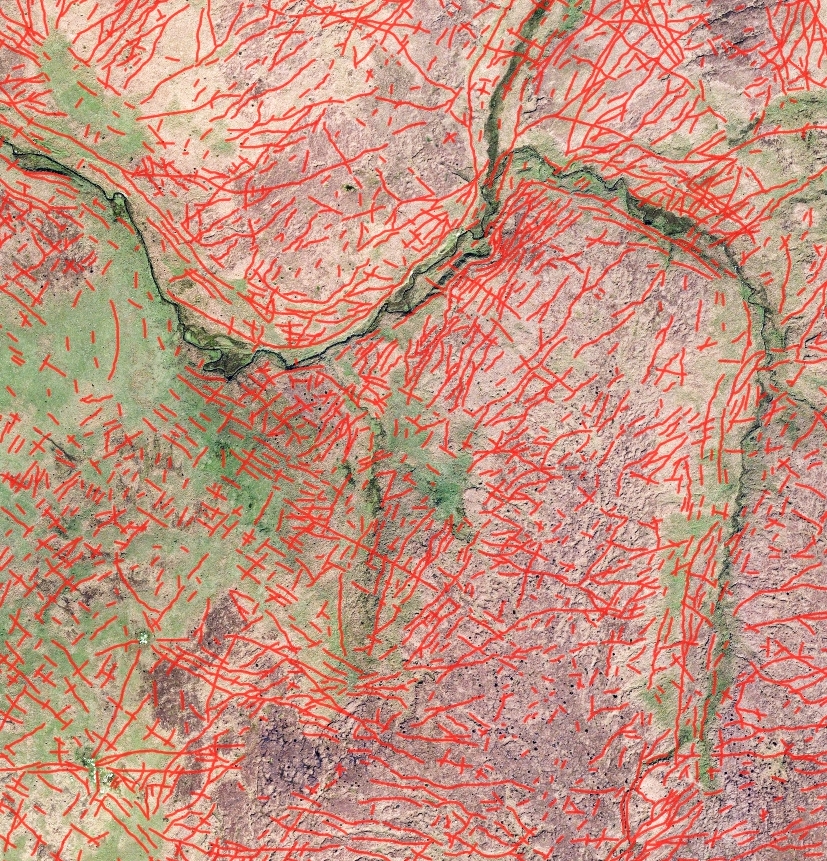

Image: A

satellite view showing animal and human tracks and the

typical patterns they form over an open landscape on Dartmoor just south

of Hexworthy - the ancient routes of Devon would have been formed in this way too. This kind of pattern is the same in every corner of the world!

When we go for a walk across an open moorland we will often choose the

easiest way, the way with a view of where we are

going - the way that leads to something in the landscape that we are

curious about, or have been told is there. As we

travel up a hill we might take the easiest route up a valley rather than

straight up the steepest side of the hill to

get to the top. When coming down from a high point we might take the

quickest way to where we are going, to where we

can see or to a place we know. Sometimes we might have no choice

and have to get from A to B in the best way we can because there is no

other way or because the alternative is a much

longer journey.

So we can see how these pathways would have been a compromise based on

getting from one place to another, the juggling

of hill top ridges and gentle valleys. These paths were dictated in most

part by the topography of the land and how early

people and animals found it best to move across it but we also have to

remember that at times in ancient history that

much of the land was covered with trees so getting a view of what was

much further ahead might have been tricky at times! Not to forget also that

people could only really travel back then during daylight or a well

moonlit night. Think about how in remote jungles or deserts of the world

today

how people rely on guides from tribes to advise them of the best way.

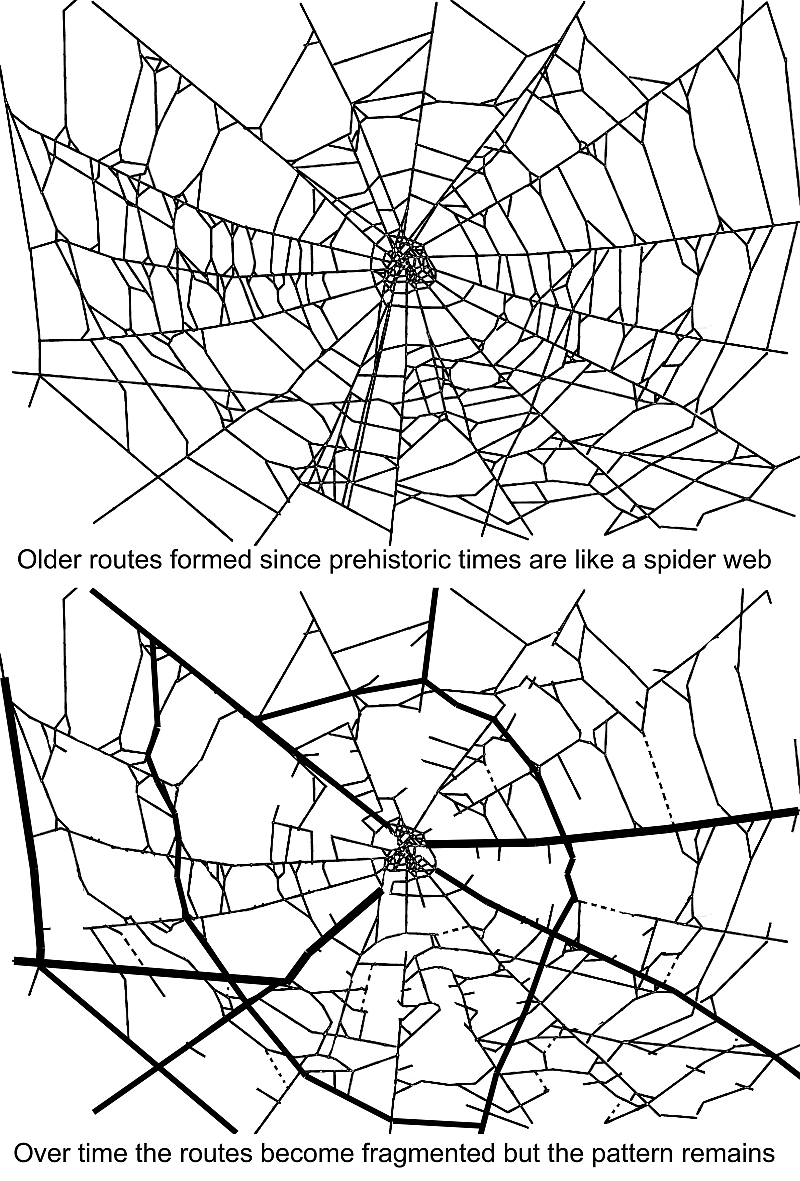

Over the centuries the forming of trackways would have been a bit like the patterns created when a spider weaves a web but the continual wear and tear of the landscape by generations of people, changes of use, changes in culture and land ownership would have gradually fragmented the layout.

From

my observations of maps it looks like the Roman's would have reused

many older existing tracks and upgraded them as well as making their own

new roads which fit in with the topography based on their own

techniques and planning. The more modern courses of railways and main electric

pylons sometimes seem to also coincide with the routes of ancient Roman roads in hilly

terrain.

After

the Roman times in Britain we pass through various stages in history

with Viking, Saxon, Norman, the Medieval, Tudor and more modern times. There were

huge changes over many hundreds of years. The Saxons had methods of

managing the land with small strip fields and the Normans had more open

square plots of land. From the 19th century the opposite occured and many hedges were ripped out to make bigger fields. My studies suggest to me that field

systems laid out in the Bronze Age (known as reeves) were likely still

used as boundaries and the later settlements were knitted in over the

top of these.

Over time the shaping

up of the land and the routes passing through it would have been subject to land ownership that passed from Kings, Baron's

and the Church. This would have affected the rights of ordinary people to travel along certain paths or even to be

allowed on certain land and would account for some ancient routes changing - being lost completely or some becoming more important.

Back to the Raw Map Data

The purpose of my study over the years was to grasp an understanding of the ancient framework that makes up my own

county, Devon. It is said that Devon had more roads than any other County in England! They were put there by

hard working people for a good reason, even if the majority of them are mere fragments of what they once were.

At first I scanned modern o/s maps of the area I wanted to study then traced over the contours but as you

can imagine it was exceedingly time consuming. What I needed was a map of the whole of Devon but which

showed only the contours and the coastline. Thankfully recent technology and the Ordnance Survey were

able to help by supplying me with "Opendata" which allowed me to then formulate the very map I was

always needing to work from - a clean canvas upon which I could mark my own ideas and not be influenced

by what is actually there on the ground.

The map shown here was my first basic layout which shows the entire landscape of Devon as a contour only map

upon which I added a number of very basic routes that I felt might have been

used in ancient times to get around Devon. Initially I thought it would work well to study smaller areas

but as I did this I realised I needed to zoom out more and more in order to see the big picture.

This map is zoomed in on the previous one and shows purely contour

information for the area covering the Bovey Basin, Newton Abbot, Teign

Estuary and Torquay. I had to take

dozens of small contour maps like this and stitch them all together to

get a complete map of the whole of Devon which took many hours.

Another part of the overall study of Devon routes I chose to do was to

mark up the contour maps to show three main systems which were:

Ridge routes, Valley routes and Cross-Link routes. This was just to form

a simple framework based on the natural topography of the County and using this to try and see if there was any pattern to it and whether what I guessed actually did play out in real life on the maps.

The problem I then had with this was that while in many instances I could identify ridge top and valley routes

I began to see that this method would not work quite so well as I had first thought! This would be especially

the case where terrain was much flatter and it was not so easy to determine where routes would have gone. So I then

decided to enbark on another branch of this project by stitching together all the Historical O/S Maps 1:25,000 series.

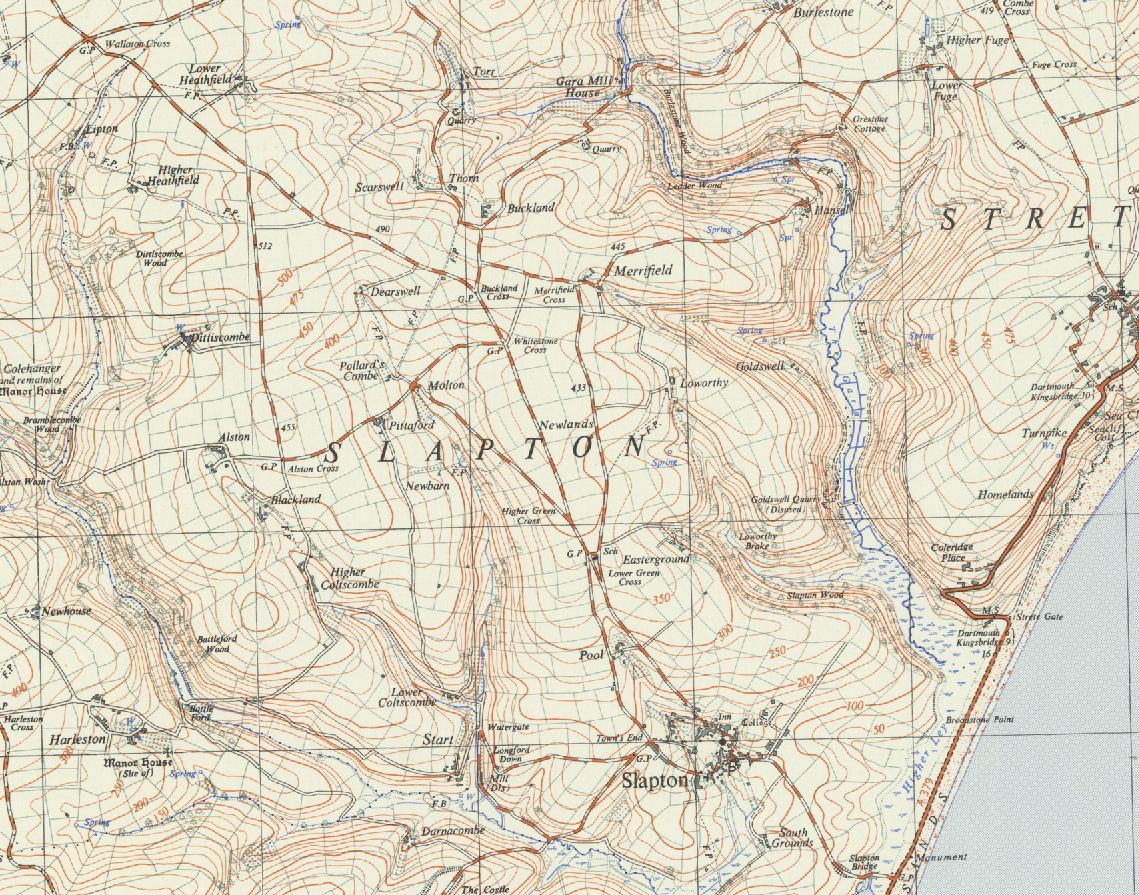

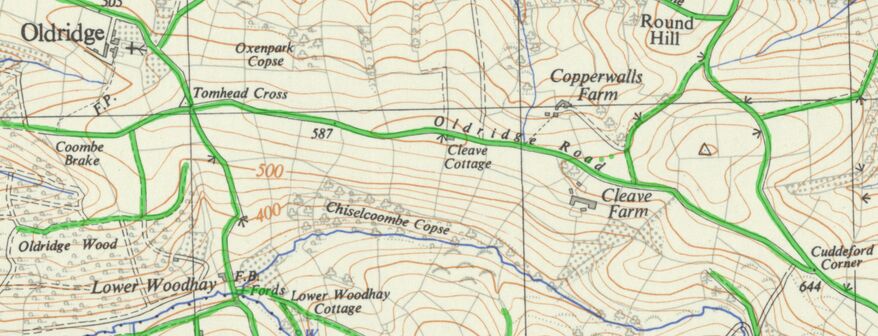

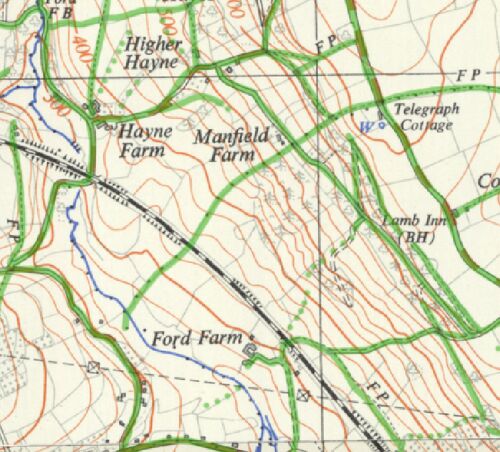

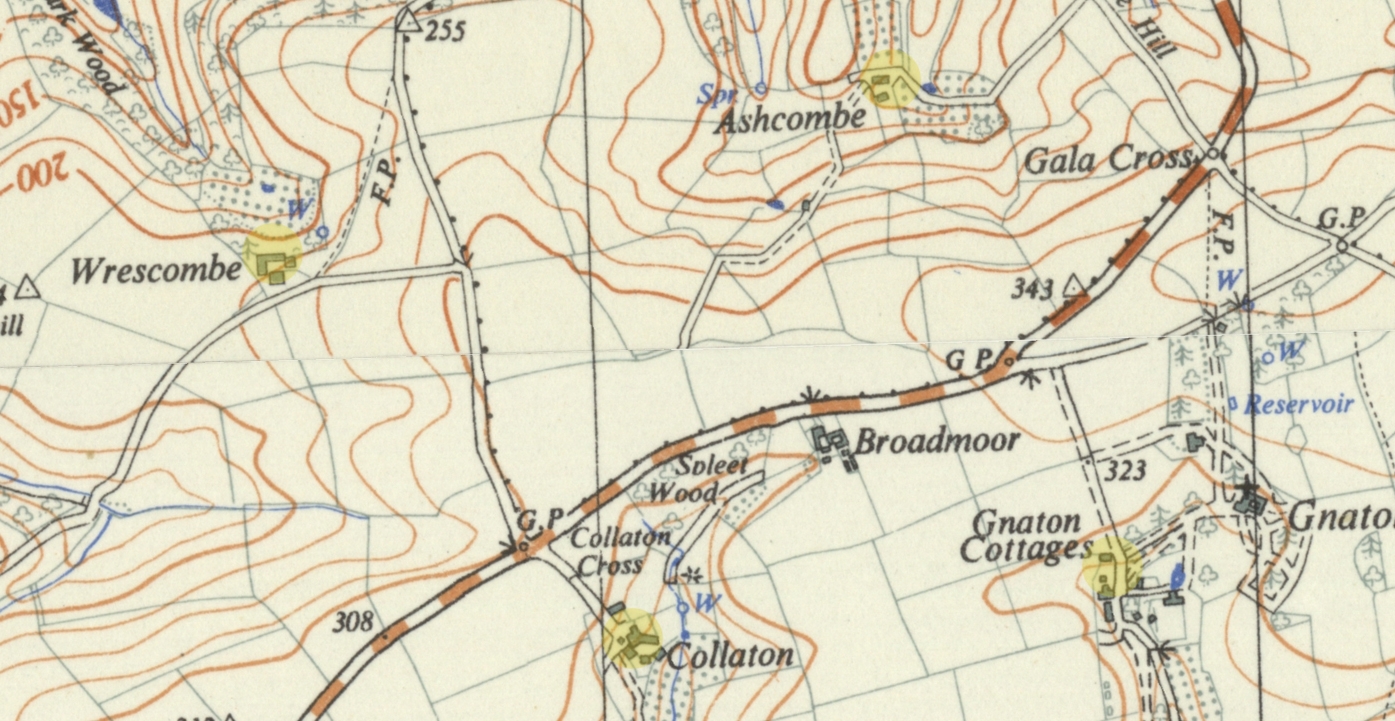

USING 1:25,000 O/S HISTORICAL MAPS

Having first used maps containing

just the contour information for Devon I then decided to move on to

using Historical O/S Maps 1:25,000 series that were

available online. These maps were very helpful in that the contours are

clearly shown and the other features are all marked on them in a simple

way that was

easy to see, not being cluttered with too many colours or fancy shading

and because the maps are mainly pre-WW2 the modern roads and features

are not shown.

I used these maps and stitched them together to form much larger regions

of Devon onto which I could then apply the previous knowledge I had

gained from the simpler contour maps. This proved to be

very useful because although the roads and fields were shown on them already I

could actually see in my minds eye certain patterns that had arisen

because of the topography. I could also see how my best logical guesses compared to the actual real maps which record what is in the landscape.

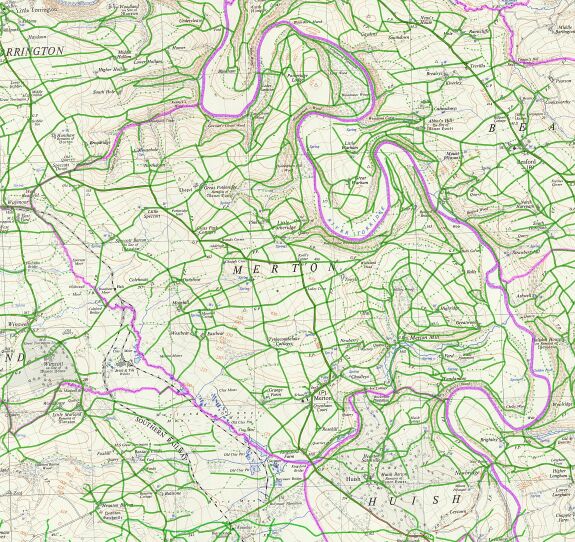

Having prepared the maps of Devon I drew in the finer

details of every possible track no matter how trivial it seemed.

I used green lines for this as in this map of the Merton area in North West

Devon. This begins to highlight certain patterns (like that of a broken spider web) and with your mind you can see where the original lines might have been.

EXAMPLE 1. The Ridge-Top Route

EXAMPLE 2. Junctions on a Flat Top Hill

EXAMPLE 3. Routes up the Steep Hillside

Observations of the Field Systems

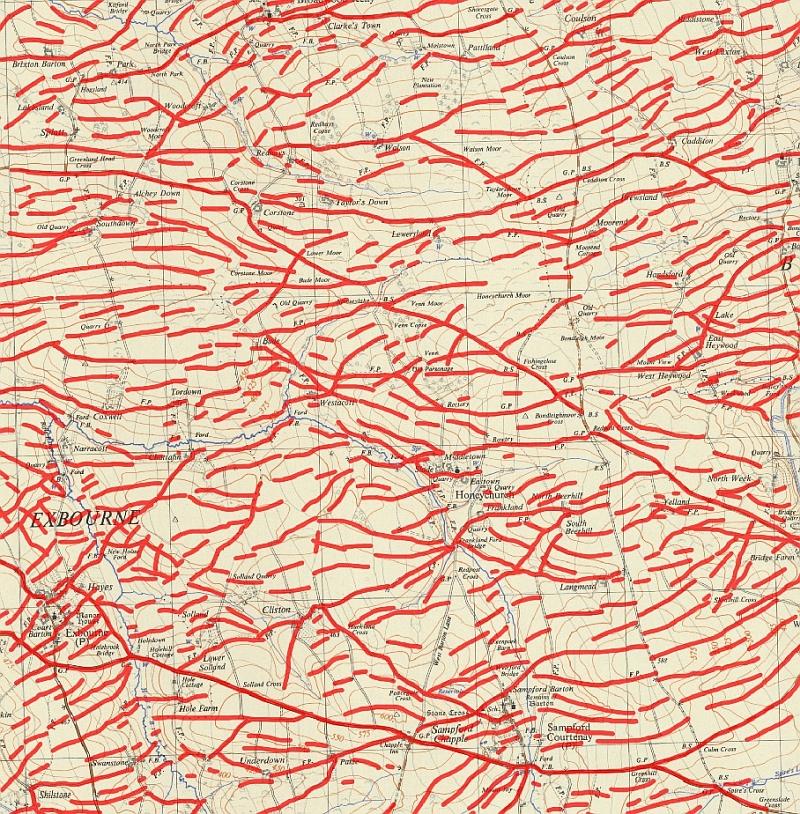

Map: Shows the rough east-west flow pattern of field systems (possible reeves) through the landscape near Honeychurch. There are also rough north-south flows as well, not shown here for clarity.

At this stage of my study I began to think more about reeves and I checked them out on various maps and lidar images. They seem to occur as long strips flowing through the landscape as parallel lines. They can run on for many miles across Devon and oddly they seem to pass over valley's at strange angles ignoring the topography as if it were flat ground. This puzzled me more and more until I realised that the reeves seem to be set out based on the more dominant topography in the landscape and are set out relative to that which is why they ignore and cross over small valleys in this way.

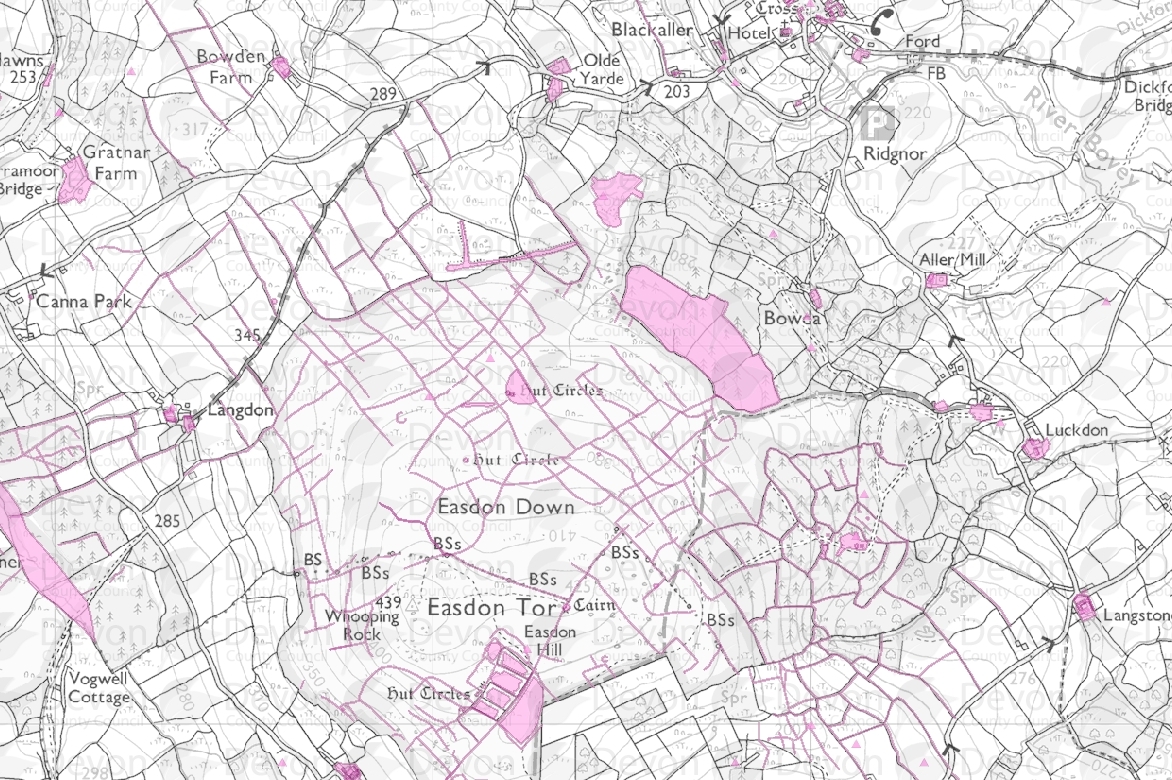

Map: Shows how I followed the field system flow based on the Bronze Age reeve idea I had and you can see how I coloured the map to make it easier to see how even older passage across the landscape might have been set out.

During 2018 and onwards I decided to do a whole new mapping layer across the Devon landscape based on this reeve idea and this really did open my eyes and a lot of things I had previously not understood suddenly made sense. I began to focus more on the flow of fields across the landscape rather than the tracks because in part they held a lot of the older web of patterns. In order to do this I first drew them all in using a single colour but I could not then work out which ones went where and which ones might be important so I did it all again taking many weeks using coloured groups of lines and this helped a lot. I did most of Devon though I never completed the Exmoor area nor the centre of Southern Dartmoor.

Map: Satellite image shows how I mapped the now open landscape of the whole of Northern Dartmoor tracing off any lines I could see in the landscape including modern routes, footpaths, animal tracks and traces of old routes revealed in the landscape by vegetation growth.

I also decided that if I was to see the whole picture of Devon that I would somehow need to work out what might have been routes across the open landscape of our modern Dartmoor long ago. I had no idea whether this would work but using thousands of joined satellite images I was able to visually see and draw on every mark and line. And to my amazment I could see the same layout of tracks over the bare moorland that followed the same pattern of the reeves even though they were absent. I was able to draw in what I believe to be the original paths over the moor through time and it did fit very well into the more detailed maps around the moor.

Map: A more realistic ancient route pattern for the whole of Devon revealed.

During 2022 and 2023 Ifinally got to the stage where I could simplify the coloured maps I had done to try to reveal a larger more structure grid of possible trackways around Devon which I think might have been set out mainly in the Bronze Age. I might have a few of these wrong but this map seems to make good sense as people could travel in very long lines for many miles and each intersection would create a cross road which would be good for navigation too, not forgetting Devon does have many ancient cross roads too.

Discover the magic of Studio Devona!

Immerse yourself in traditional crafts, various creations and interests rooted in and inspired by the ancient landscape of Devonshire.

Get in Touch with

Devona

Lea-Croft Cottage, Cheriton Bishop, Devon. EX6 6JH